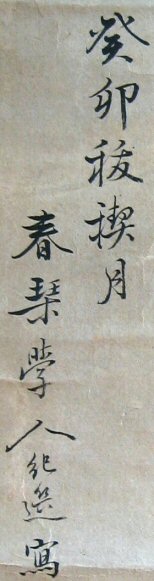

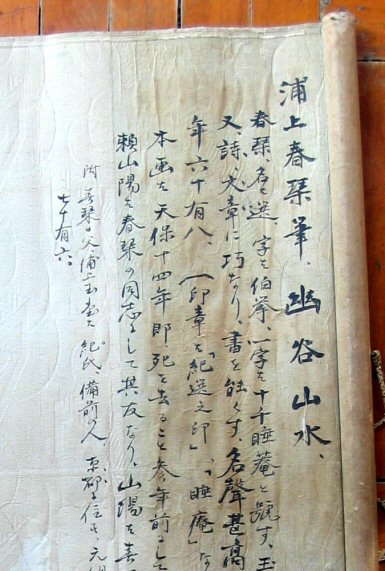

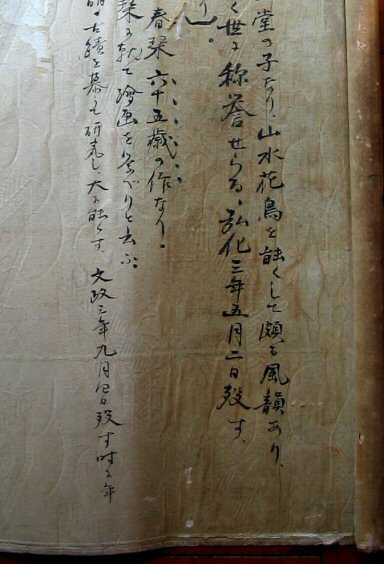

The following are biographical notes of the painter written down at the back of the painting by the previous owner :

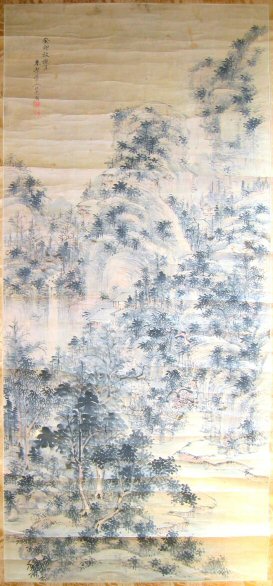

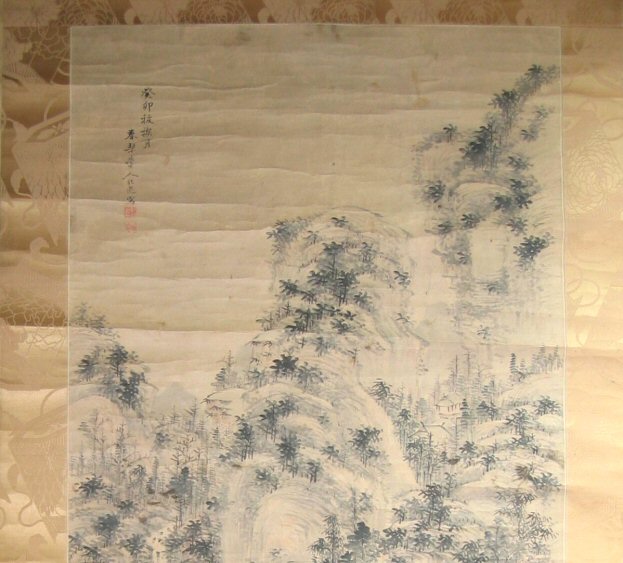

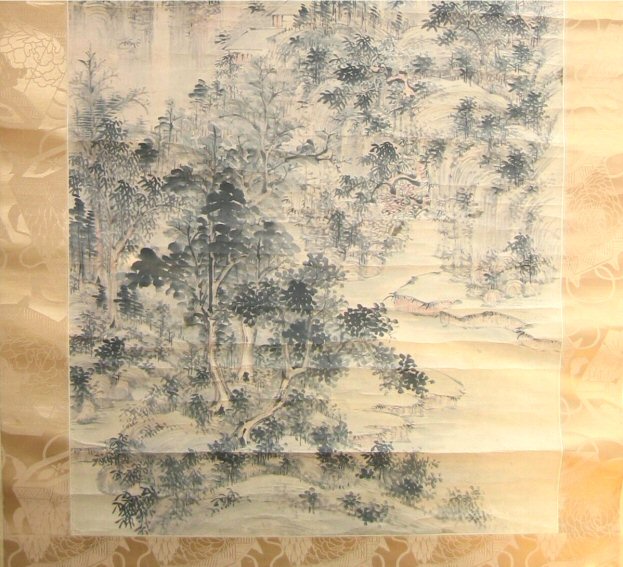

Scroll of “A Desolate Valley and Surrounding Landscapes”

Painted by Japanese 19c Master Artist Uragami Shunkin (1779-1846) in Year 1843

日本江戶時代藝術大師浦上春琴 (1779-1846) 1843 年作《幽谷山水》立軸

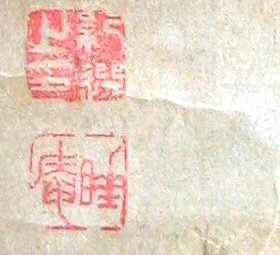

Uragami Shunkin 浦上春琴 (1779-1846)

N. Uragami Sen 浦上選 A. Hakukyo Go. Shunkin Suian Bunkyotei S. Nanga school. Studied under his father, Gyokudo. L. & C. Born in Bizen. Lived in Kyoto. Nevertheless, his style differs from that of his father's because he studied Chinese paintings of the Yuan and Ming dynasties. Sp. landscape, flowers-and-birds.

In the 19c, a generation of Japanese painters or bunjin began to paint with less innovation in styles that more closely resembled Chinese models. This conservative trend is obvious in the works of Nakabayashi Chikutou 中林竹洞 (1776-1853), Yamamoto Baiitsu 山本梅逸 (1783-1856), and Gyokudou's son, Uragami Shunkin 浦上春琴 (1779-1846), who limited their range of compositions and refined their brushwork to comform with designated Chinese models. As a result, bunjinga produced from the mid 19c exhibits a uniformity of style and composition.

浦上春琴 (1779-1846)

安永8年生。弘化3年5月2日歿,享年68。

江戶時期大畫家浦上玉堂之長子。又名選。通姓紀, 字伯舉。俗稱浦上喜一郎、別號睡庵、二卿、文鏡亭等。自幼得到父親浦上玉堂 (1745-1820)教授繪畫。

父親浦上玉堂 ,是在池大雅 (1723-1776) 和與謝蕪村 (1716-1783)死後,南畫界陷入沈寂不振的時候,再度振興南畫的畫家,他的個性獨特,畫風自立。曾任備前 (岡山縣) 池田家的藩士,擅長陽明學與漢詩文。得意於琴藝,手上的名琴取名為玉堂清韻,並以玉堂琴士為號,其兩子亦以琴為名,長子取名春琴,次子取名秋琴。

寬正六年 (1794) ,日本推行寬政異學的禁令,浦上玉堂因為研究陽明學說的關係,恐怕有危險,於是脫離藩主,帶著春琴與秋琴兩子遍遊各地名勝、寫生、並研究以及臨摹古畫蹟等。後定居京都,與賴山陽等文化人交往密切。但是,浦上春琴因為與中林竹洞 Nakabayashi Chikutou (1776-1853) 、山本梅逸 Yamamoto Baiitsu (1783-1856)等一派畫家推祟宗元畫法,作畫亦以宗元畫為範本,故其畫法趨於保守,自成一格,與其父自由奔放之畫風,大為不同。此畫成於浦上春琴氏 晚年65歲時,畫面充斥著宋元畫風,堪稱浦上春琴氏登峰造極之作。

Click Here to See Other Japanese Paintings

Click Here to See Other Paintings

Click Here to Go Back to Homepage

===========================================================================================

bunjinga 文人畫

Chinese: wenrenhua. Lit. 'literati painting.'

A type of painting in China, Korea, and Japan. In Japan, the term bunjinga is often used synonymously with the term *nanga 南畫. In addition to mastering classical literature, history, and philosophy, Chinese scholars practiced calligraphy and painting. The style of painting developed by literati--featuring personally expressive, apparently casual brushwork, primarily in *sumi 墨 ink--was somewhat different from the more polished, detailed styles generally practiced by professional painters. Chinese literati painting eventually was designated as "Southern School painting" (Ch: nanzhonghua, Japanese: *nanshuuga 南宗畫). Landscape and selected plants such as bamboo and orchids became dominant subject matter or themes, reflecting in part the scholar's desire to commune spiritually with nature. Some knowledge of the Chinese literati painting tradition existed in Japan during the Muromachi period (1392-1568), but it was not until the middle of the Edo period (1600-1868) that circumstances encouraged it to become a full-fledged artistic movement. Interest was nurtured by the Tokugawa ?川 shogunate's promotion of Confucianism and Chinese culture. However, in Japan the concepts of bunjin 文人 and bunjinga were broadened. Chinese wenjen were members of a scholar-gentry class who normally held positions in the bureaucracy, but Japanese bunjin were men and women of varied backgrounds, social classes, and occupations. Travel to China was forbidden, so Japanese learned the fundamentals of literati painting through studying imported paintings and woodblock-printed painting manuals, and occasionally through direct contacts with visiting Chinese artists such as I Fuzhou 伊孚九 (Jp: I Fukyuu fl. first half of 18c). Their models were mixed, including works by Ming and Qing-dynasty professional painters, as well as by true literati. Japanese practitioners did not always distinguish between the Northern lineage, hokushuuga 北宗畫, and the Southern lineage, especially during the early phases of bunjinga. Artists of the Kanou school, *Kanouha 狩野派, also painted in a Chinese-derived style, but in general Japanese bunjin in the 18c regarded the newly introduced Southern styles as superior and dismissed academic Kanou work as superficial and stereotyped. Among the early bunjinga pioneers were Gion Nankai 祇園南海 (1677-1751), Yanagisawa Kien 柳?淇園 (1706-58), and Sakaki Hyakusen 彭城百川 (1698-1753). Nankai and Kien belonged to the samurai 侍 class and had official governmental posts; they painted as a hobby and thus somewhat resembled China's scholar gentry. However, Hyakusen was a townsman and a professional painter. In China, literati theoretically painted for their own pleasure and did not market their works, but in Japan many bunjin artists like Hyakusen openly made painting or teaching their livelihood. The patrons for bunjinga were people from a variety of backgrounds who were interested in Chinese culture. Japanese bunjin artists generally remained closer to Chinese models during this first phase, although the artistic styles vary dramatically, ranging from austere ink landscapes and bamboo paintings to colorful figures and decorative flower-and-bird paintings, *kachouga 花鳥畫. Bunjinga steadily grew more popular and by the late 18c and early 19c was being practiced by a broad spectrum of artists in provincial Japan, as well as in the urban centers of Kyoto, Naniwa (Osaka), and Edo. Three artists who stand out are Ike no Taiga 池大雅 (1723-1776), his wife Gyokuran 玉瀾 (1727-1784), and Yosa Buson 與謝蕪村 (1716-1783). They are credited with transforming an essentially Chinese tradition into one having a Japanese flavor. In particular their work features a bolder sense of compositional design, less brushwork layering, more patterned application of brushstrokes, and a more comprehensive distribution of ink and color. The decreased sense of spatial depth is offset by provocative surface textures. Moreover, unlike their Chinese contemporaries, the early generations of Japanese bunjin felt free to experiment with a range of stylistic models. This spirit of individualism is well represented by artists such as Uragami Gyokudou 浦上玉堂 (1754-1820), Okada Beisanjin 岡田米山人 (1744-1820), and Tani Bunchou 谷文晁 (1763-1840). The following generation of bunjin began to paint with less innovation in styles that more closely resembled Chinese models. This conservative trend is obvious in the works of Nakabayashi Chikutou 中林竹洞 (1776-1853), Yamamoto Baiitsu 山本梅逸 (1783-1856), and Gyokudou's son, Uragami Shunkin 浦上春琴 (1779-1846), who limited their range of compositions and refined their brushwork to comform with designated Chinese models. As a result, bunjinga produced from the mid 19c exhibits a uniformity of style and composition. A similar phenomenon had occurred in Qing-dynasty academic painting. However, despite efforts to be faithful to their Chinese mentors, later bunjinga is still characterized by a Japanese sense of surface design. Occasionally some late 19c bunjin ignored the prevailing norms and painted in boldly idiosyncratic manners, but they were exceptions. Bunjinga continued to be enthusiastically practiced and collected into the early Meiji period (1868-1912), but by the 1880s interest had begun to fade in response to growing fascination with Western oil painting, *youga 洋畫, and the developing modern style of Japanese painting, *nihonga 日本畫. With the West replacing China as the culture to emulate, trends in education and art followed suit, and bunjinga ceased to be a viable painting tradition. ===========================================================================================================

nanga 南畫

Lit. southern painting. An abbreviation of *nanshuuga 南宗畫, which refers to painting of the "Southern School" in China. Nanga is often used synonymously with *bunjinga 文人畫 to describe the painting tradition inspired by Chinese literati painting that flourished in Japan during the 18c and 19c. While scholars tend to prefer one or the other, neither term is the exact equivalent of its Chinese counterpart. To begin with, Japanese bunjin artists were not members of the scholar-gentry class, but came from varying social backgrounds. Bound together by shared interests in literati culture, they formed societies and study groups, devoting themselves to learning to read Chinese, composing poetry in Chinese, and painting in Chinese styles. However, while artists learned by copying Chinese paintings and illustrations in woodblock-printed manuals, Japanese nanga is stylistically quite different from Chinese literati painting. There is greater diversity of subject matter and style, due in part to the fact that models included professional paintings (Northern style or *hokushuuga 北宗畫) as well as literati paintings (Southern style). The Japanese did not feel bound to follow established Chinese traditions and felt more free to improvise. This, coupled with native preferences, resulted in paintings with bold compositional designs, free brushwork, and a playful spirit,qualities not usually found in classical Chinese literati painting. While the starting point was the Chinese literati tradition or "Southern School," in Japan nanga was more broadly interpreted and it embraced more than strictly Chinese literati styles.

nanshuuga 南宗畫

Ch:nanzhonghua. The Southern School of Chinese painting. Composed of literati (scholars) as opposed to the Northern School (*hokushuuga 北宗畫) of Chinese painting which was composed of professional artists. This division of painters into two lineages was championed by the scholar-artist-theoretician Dong Qichang 董其昌 (Jp: Tou Kishou, 1555-1636). The terminology was borrowed from Chan 禪 (Jp:Zen) Buddhism, which had also split into Northern and Southern schools. Whereas Northern Chan practiced methods leading to gradual enlightenment, the Southern branch promoted the idea that enlightenment could occur more suddenly. Dong employed these divisions to distinguish different approaches to painting: literati or scholar-artists were put into the "Southern School" and professionals into the "Northern School." The former generally painted with ink and emphasized personally expressive brushwork, while "Northern School" artists tended to use more color and painted in more formal, detailed modes. The classification of artists was based on social status as well as painting style, and because scholars themselves were the art critics, the "Southern School" was touted as superior. Among the major "Southern School" painters were Wang Wei 王維 (Jp: Oui, 699-759), Dong Yuan 董源 (Jp: Tou Gen, mid 10c), Huang Gongwang 黃公望 (Jp:Kou Koubou, 1269-1354), Ni Zan 倪贊 (Jp: Gei San, 1301-74), Wu Zhen ?鎮 (Jp: Go Chin, 1280-1354), Wang Meng 王蒙 (Jp: Ou Mou, 1308-85), Shen Zhou 沈周 (Jp: Chin Shuu, 1427-1509), and Wen Zhengming 文?明 (Jp: Bun Choumei, 1470-1559). Wide-scale emulation of "Southern School" painting occured in Japan during the 18c and 19c, when interest in Chinese literati traditions peaked.

Click Here to See Other Japanese Paintings

Click Here to See Other Paintings

Click Here to Go Back to Homepage